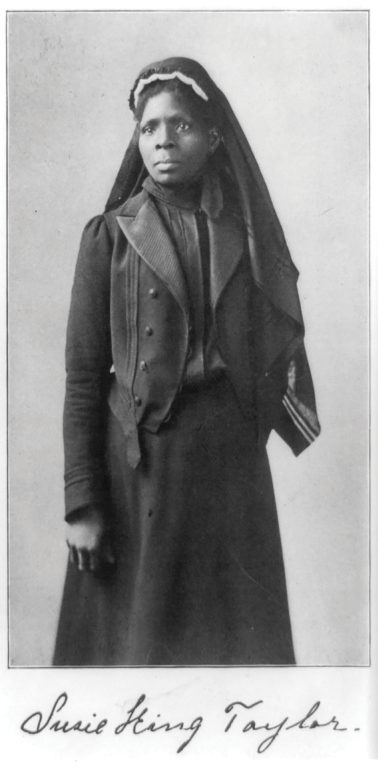

Born enslaved in 1848, Susie King Taylor became a legendary educator, nurse and author. Hers is the only square named for a woman or an African American.

Written by TRELANI MICHELLE

SAVANNAH WOULDN’T BE SAVANNAH without its verdant squares laid out in a grid by General Oglethorpe. Of the 22 original remaining squares, the names represent familiar figures from American history — names like Oglethorpe, Washington, Madison and Pulaski.

“We got 22 squares that don’t look like the majority population here,” Patt Gunn, co-founder of the Susie King Taylor Center for Jubilee and co-chair of the Coalition to Rename Calhoun Square, wrote in a 2021 letter to Savannah Mayor Van R. Johnson. “Those 22 squares are named for men who were Confederates and American Revolutionaries. The numbers are not balanced.”

On Aug. 24, 2023, the Susie King Taylor Center for Jubilee made history when Calhoun Square, named for former Vice President John C. Calhoun, a staunch slavery advocate, was renamed Taylor Square. This was the first time in 140 years that a square was renamed. Taylor Square, located at Abercorn and Wayne streets (serendipitously bordering East Taylor Street, albeit no relation), is also the only square named for a woman or an African American. So, what makes Taylor’s name a name to know?

Born enslaved on Aug. 6, 1848, Taylor moved to Savannah from Liberty County at 7 years old to be raised by her grandmother, a savvy businesswoman who was freed before Emancipation. Adamant about her grandchildren being educated, Taylor’s grandmother arranged for Taylor and her brother to secretly learn to read and write from a fellow free Black woman. Fearing that Black literacy threatened the slave system, it was illegal for Black people to read and write, and it was a crime to teach them, so this was a very risky endeavor.

A fast and eager learner, Taylor studied with four teachers (the latter two being white children) before completing her “school” studies.

At 14, she began her career as an educator for the Union Army on St. Simon’s Island. To keep her around, in August of 1862, the Army enrolled her as a laundress, though she did very little cleaning because she was too busy cooking for and nursing ill and injured soldiers, making her the first Black nurse in the Civil War.

After the war, Taylor became one of Savannah’s first legal educators for Black students when she opened her home on South Broad Street (now Oglethorpe Avenue) as a school, charging $1 per pupil.

“Susie King Taylor was all about healthcare and education,” says “Sistah Roz” Rouse, also co-founder of the Susie King Taylor Center for Jubilee and co-chair of the Coalition to Rename Calhoun Square. “And what [issues] are we dealing with today? Same thing: education and healthcare.”

In 1902, Taylor self-published “Reminiscences of My Life: A Black Woman’s Civil War Memoirs,” making her the first Black woman to self-publish her memoirs and the only woman to publish a book about her experiences during the Civil War. Despite Taylor’s accomplishments, getting Calhoun’s name replaced with Taylor’s wasn’t a walk in the square.

In 2020, Gunn and Rouse were approached by a tourist who claimed that Calhoun Square was a burial ground of enslaved people. They reached out to the city’s Director of Municipal Archives Luciana Spracher and learned that Calhoun was actually a burial ground for poor whites and sailors who weren’t Savannah natives, while the enslaved burial ground is located in Whitfield Square. Residents of the latter square warned Gunn and Rouse that removing Whitfield’s name would be difficult since he co-founded The First Congregational Church located there.

Gunn says her 30 years in social justice taught her the art of compromise. Plus, she points out that Calhoun had already been taken off over 100 different places around the nation, including a lake in Minnesota. After agreeing to go after Calhoun instead of Whitfield, Gunn and Rouse requested that the square be renamed Sankofa — a Ghanian word and symbol that means fetching wisdom from the past to positively inform the present and future.

The renaming of public spaces in Savannah requires a 51 majority vote from the neighborhood, and supportive neighbors preferred the square be named after a local person. The Susie King Taylor Center for Jubilee was once again willing to compromise. “Sistah Roz educated them on who Susie King Taylor was and the neighbors fell in love with her,” Gunn says.

Still, change doesn’t happen overnight. Several times after the Susie King Taylor Center for Jubilee attained the 51% vote but a home would sell before the City Council could respond to the proposal — meaning there was a new neighbor and a new voter to win over. Nevertheless, they persisted.

“If the policies don’t work, go to the authorities in charge and say you need to change your policies because they are not working for the citizens of the 21st century,” Gunn says. “That’s what we did.” A new policy change now allows the City Manager to use their discretionary power to unname public spaces. After three years of meetings, hearings and petitions, including an invitation for other names to be nominated, Taylor Square was official.

“This isn’t something that we can take credit for. It was the methodologies of Civil Rights leaders,” Gunn shares. “And it’s a blueprint for future generations and other cities.”

In true Sankofa spirit, the Susie King Taylor Center for Jubilee is still working to get a statue of Taylor installed in the square, as well as benches inscribed with the square’s other nominations, including The Seven Sisters, Creek Nation, W.W. Law, George Leile, Major Clayton Carpenter and Leo Center.

Taylor, who wasn’t even able to collect a veteran’s pension because she was listed only as a laundress on paper despite her varied and vital contributions, now has a River Street ferry boat named for her, a Savannah-Chatham K-8 charter school, The Susie King Taylor Women’s Institute and Ecology Center and a historical marker in Midway, and now, Taylor Square.

“What would Susie King Taylor be doing today?” Rouse asks. “Educating and teaching, which is exactly what we’re doing.”